A Short Guide to Understanding Female Genital Cutting

Female genital cutting (FGC) used to be an issue that only feminists and anthropologists discussed. Over the past decade, however, the issue has been rising in the global agenda. Just this past month, a newKurdistani film on FGC made waves in the international media, a podcast about the issue was broadcast by the Guardian, and UNICEF held a global conference dedicated to ending the practice. Even with increased publicity around the issue, many global audiences do not yet understand the complexities behind FGC, and effective approaches to change the practice. Below, Dalberg Dakar’s Tania Beard presents an overview of FGC, with a focus on the situation in Senegal.

Female genital cutting, also known as female genital mutilation, is the partial or total removal of a girl’s external genitalia, often with a rudimentary blade. FGC is believed to have originated in Eastern Nubia, today’s Egypt and Sudan. According to some accounts, the practice began with Egyptian pharaohs, who cut the women in their harem to ensure fidelity. This practice became associated with high status, and filtered down through all levels of society as girls were cut in the hope of moving up the social strata.

Origins of Female Genital Cutting

Most often, women conduct FGC procedures. They are frequently professional community cutters or qualified doctors.

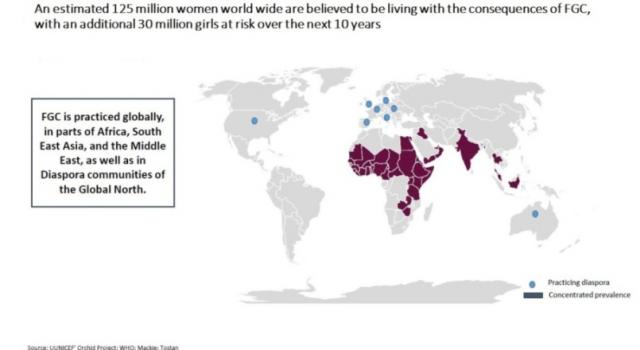

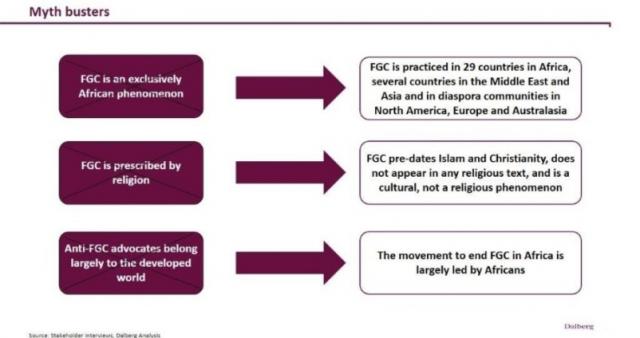

Communities in parts of Africa, South East Asia and the Middle East practice FGC. Certain Diaspora groups in the Global North also practice FGC, as they tend to cling to cultural traditions, even after their home communities begin to let them go.

One of the greatest misconceptions surrounding FGC is that the procedure has a strong link to Islam, a relationship practitioners often cite as justification for cutting. In reality, FGC pre-dates the advent of Islam and Christianity, and diverse religious communities practice it today.

Why do communities practice FGC?

Often, practicing communities have multiple justifications for FGC. In one of the most conservative areas in southern Senegal, one imam told me that women are cut because it makes them healthier, more beautiful, and crucially, more faithful. Were it not for the cutting tradition, he said, “Women would be jumping on top of all the men.” The most widely held justification for FGC, however, is that the practice is a deeply ingrained tradition.

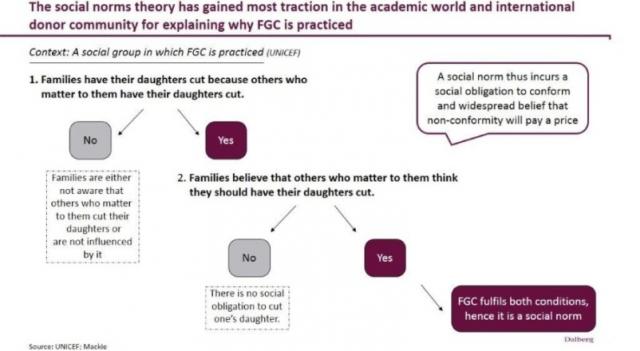

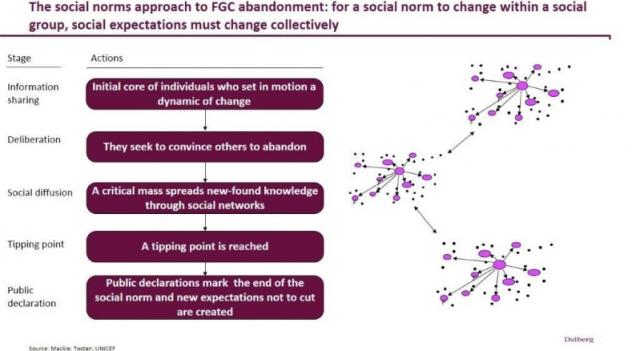

The social norms theory suggests that the practice of FGC is driven by a community-wide social obligation to cut. In Senegal, the social norms approach can help us understand why FGC persists. As a social norm, FGC is based on social expectations to cut and thus provokes positive sanctions when enacted, and negative sanctions when avoided. Where FGC is linked to marriageability, the community tends to believe that girls who are not cut will not get married and therefore, will not have a place in the community. Understanding FGC as a social norm thus has important implications for mobilizing effective interventions, though it is just one approach and its effectiveness varies depending on local context. Graphic used courtesy of UNICEF’s ChildInfo.org.

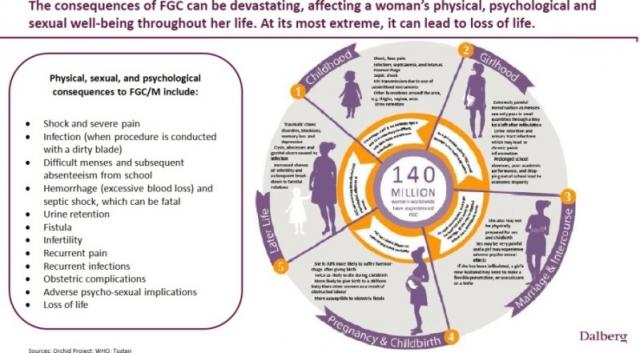

What is the harm of FGC?

In addition to the adverse health effects associated with FGC, the practice is internationally recognized as a violation of the human rights of girls and women.

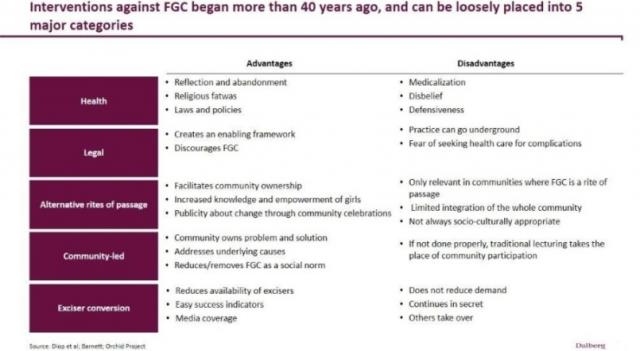

What is being done to stop FGC?

Interventions designed from a single angle often are not comprehensive enough to elicit large-scale change. For instance, interventions in Egypt that approached the practice through the lens of health concerns have contributed to the medicalization, rather than elimination, of the practice; in some areas, popular sentiment became: “If it is bad for us, then we will go to a doctor to do it.”

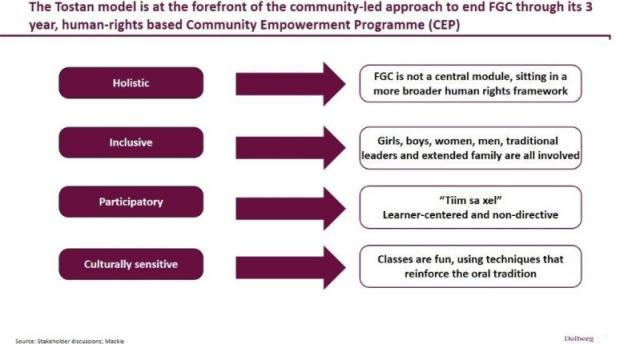

Tostan is one organization working to end FGC. Their model uses a three-year informal education program that is holistic, taught in local languages, and based around a series of discussions facilitated by a trained volunteer – often a member of the village or wider ethno-linguistic group.

These discussions do not focus exclusively on FGC, but rather couch the practice within a wider human rights framework including topics such as health, hygiene, human rights and responsibilities, problem-solving, literacy, and community management. When Malicounda Bambara was the first Senegalese village of to stand up to publically abandon the practice of FGC in 1997, it was an unanticipated consequence of the Tostan program rather than one of its stated objectives.

Social norms approaches, similar to the Tostan model, rely on social diffusion, or the process of acquiring critical mass. In Senegal, even if individuals within the practicing community wish to put an end to the cutting tradition, they are unlikely to succeed on their own. Rather, social expectations in the wider community must change through a process that often involves both men and women, village authorities, groups who traditionally inter-marry, and even the Diaspora. In the case of Tostan, social diffusion often culminates in a series of public declarations marking the end of the social norm and creating new expectations not to cut.

When can we expect FGC to end?

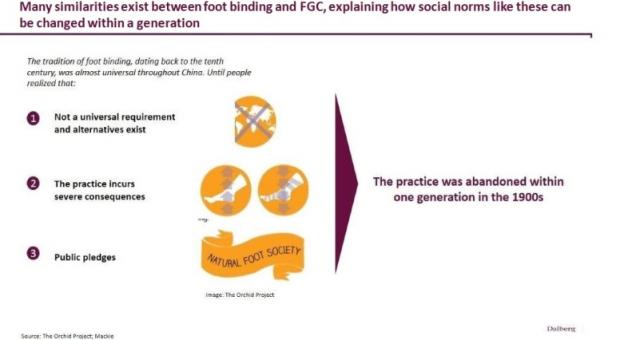

Foot binding, another practice driven by social norms, was a dangerous, debilitating and painful convention practiced in China from the tenth century to the 1900s. Communities suggested the practice would ensure a good marriage, uphold women’s virtues, and guarantee the honor of her family, not unlike FGC. The practice of foot binding was abandoned in one generation through education and a series of public declarations, suggesting that FGC could see a similar demise.

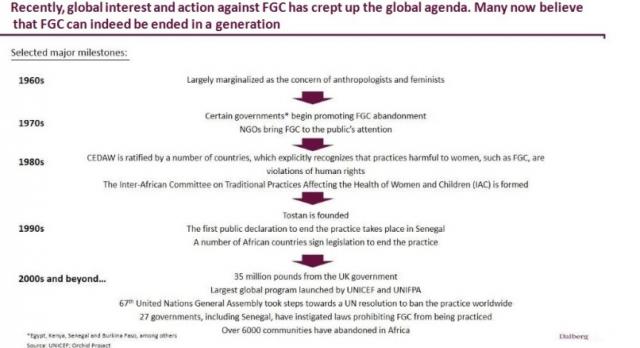

Over the past 50 years, FGC has moved from a fringe concern to an issue on the radar of the wider development community.

Tostan, The Orchid Project, Sister Fa, and Daughters of Eve have all helped drive the movement to bring FGC out of the shadows. These four organizations use an array of approaches to change, from feminist-driven to social norms-influencing, as they work to end the practice of female genital cutting.

Ending FGC is one important step to advance the status of women worldwide. To learn more about Dalberg’s gender-related work, click here.

Tania Beard is a consultant in the Dakar office of Dalberg Global Development Advisors.

Related News

- FGM raises its ugly head in Sri Lanka with Kerala Support

- #February6th: The International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation (#FGM): Celebrating Victories

- Efua Dorkenoo OBE, the ‘incredible African female warrior’, has died

- MEET A DEFENDER: DR ISATOU TOURAY

- New study in Oman shows high prevalence of FGM all over the country