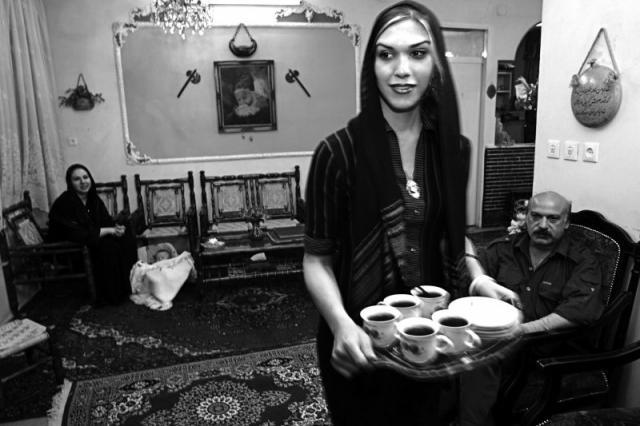

Trans[ition] in Iran

By Rochelle Terman

TEHRAN, Iran—When Shadi Amin was growing up in pre-revolutionary Iran, she began experiencing sexual feelings toward other girls. “I thought there was something wrong with me,” she says. “I thought, maybe I should change something.” By “something,” Amin was referring not to her identity or lifestyle, but to her gender. “If I was that young girl living in Iran today, I would have considered having a sex change operation,” even though she has never identified with being male.

From the Spring Issue "Sex and Sexuality"

Most people who experience same-sex attraction would not immediately think to undergo sex reassignment surgery. But in Iran, the options between a homosexual existence and a transsexual existence offer little real choice. Homosexuality, under certain circumstances, is punishable by death. Transsexuality, on the other hand, is considered a legitimate health problem by the dominant legal, religious, and medical communities, for which the sanctioned cure is hormonal treatment and sex reassignment surgery. So encouraging is the Iranian government of such surgery that it currently subsidizes procedures for qualified applicants. According to research conducted by Harvard Professor Afsaneh Najmabadi, in 2012, the Iranian newspaper positive attitude Hamshahri quoted an official from the State Welfare Organization, saying that 350 million tomans ($122,000) were allocated for assisting each patient with “gender identity disorder,” a formal diagnosis of transsexuality, including some assistance for surgical treatment.

Despite the risks, Amin decided to forgo surgery and risk pursuing her same-sex attraction as a woman in Iran. In the 1980s, she fled Iran to Germany, after several arrests for her political activism and more than a year living underground. In exile, Amin founded “6Rang”—a network for lesbian and transgender Iranians. But she remained disturbed by the increasing rates of sex change surgery in Iran. “We saw this incredibly high rate of sex change surgery, and we asked, why?” Amin explains.

Indeed, all evidence suggests that sex change operations in Iran have increased both in frequency as well as in public visibility over the last decade. Iran now performs more sex change operations than any other country besides Thailand. Not only are more people petitioning for sex change operations, but coverage of transsexuality in both the Iranian and international press has intensified since 2003—all with a positive attitude about the recognition of transsexuality and the legality of sex change operations in Iran. Many Westerners were shocked that such a progressive stance could be taken by a staunchly conservative Muslim country.

Iran is unusual in the Muslim world given its paradoxical stances on sex change operations and homosexuality. While some Muslim-majority countries, such as Egypt and Malaysia, allow sex change operations, they also tend to be more lenient with regards to homosexual behavior. Iran is the only nation that at once criminalizes homosexual behavior as a capital offence while sanctioning—even encouraging—sex change operations. “We saw Western media talking about Iran as if it was a paradise for transsexuals,” says Amin, for whom the wave of Western media coverage on Iranian transsexuality inspired deeper investigation. Even though Amin is not transsexual, the subject had deep personal value: “This was my history, too,” she emphasized.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

Najmabadi, who published the first English-language scholarly text on the subject, Professing Selves: Transsexuality and Same-Sex Desire in Contemporary Iran, divulges the complex history of sex change operations in region. According to her research, some of the earliest discussions of transsexuality in Iran date back to the 1940s, while surgeries to alter congenital intersex conditions were reported in the Iranian press as early as 1930. The earliest non-intersex sex change surgery reported in the Iranian press dates back to 1973, and by the early 1970s, at least one hospital in Tehran and one in Shiraz were carrying out such procedures. But in a 1976 decision, the Medical Association of Iran ruled that sex change operations, except in intersex cases, were ethically unacceptable.

That ruling was retained until 1985 when Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa, or religious edict, sanctioning sex change operations. In fact, Khomeini first gave approval for such surgeries as early as 1964 in his Arabic master treatiseTahrir al-Wasilha, which he wrote while living in exile in Turkey and Iraq. Not surprisingly, this ruling had little political or medical influence at the time, and other leading contemporary clerics could not come to a consensus on transsexuality or sex change operations. In 1985, Khomeini, now the politically unchallenged supreme authority, reissued his 1967 fatwa on sex change surgery, this time in Persian, following years of correspondence with Maryam Molkara, a male-to-female transgendered person who finally met with Khomeini. Of course, not all religious experts, medical doctors, or government officials in Iran were (or are) friendly to sex change operations and transsexuality in general. But the sheer weight of Khomeini’s decree was enough to ratify the law. He was not only the highest religious authority, but also the leader of the most massive revolution in the second half of the 20th century.

GAMING THE SYSTEM

While Khomeini’s fatwa unilaterally decreed sex change surgery as acceptable, it offered little guidance on the mechanisms and procedures to carry it out. As Najmabadi describes, in the last 20 years, tightly interwoven disciplines have arisen within the legal, medical, and religious community around the issue of transsexuality, in an effort to fill the gaps left by Khomeini’s decree.

Today, those who wish to undergo sex change operations must navigate a labyrinth of bureaucratic processes to be certified as an “official” transsexual. This certification is crucial because it offers protection from police harassment and the risk of breaking Iran’s strict gender separation and dress laws. Once an individual is certified as a transsexual, he or she may dress in public as the “opposite” sex. Without these permits, however, individuals caught crossdressing will be considered transvestites and in violation of the law. Certification also authorizes hormonal treatment in addition to sex reassignment surgery, as well as basic state-provided health insurance, financial assistance for health and housing aid, and military exemption. It also opens the door to state-approved, post-surgical name change, which entitles the person to receive new national identity papers.

In order to receive certification, applicants must first go through what Najmabadi calls “filtering”—a legal process of gender transition that involves a four-to-six month period of psychotherapy, along with hormonal and chromosomal tests. The purpose of this process is to distinguish and segregate “true transsexuals,” for whom same-sex desires are symptomatic of their transsexuality from homosexuals, for whom same-sex desires are symptomatic of moral deviancy, seeking to “game the system.”

The concern over homosexuals “gaming the system” exists because Khomeini’s fatwa does not actually require sex change operations for transgendered people. It simply declares that medical procedures to change one’s sex are neither prohibited nor obligatory, as there is no specific guidance in the Quran. Many have interpreted this conceptualization as opening the possibility for acquiring transsexual status without being required to go through any hormonal or physical changes if they do not wish. The possibility that a transperson may occupy an “in-between” space between the genders continues to be the subject of fierce controversy in Iran. After all, Iranian legislation is grounded in the idea that only two genders exist and bases many of its regulations on this strict dichotomy. Not only does one’s sex determine family law regulations and dress, it determines which courses one can take in universities, where one can sit on a bus or train, how far one can travel, and even which door one can use to enter buildings and airports.

If you want to continue to dress like a girl but keep your male body, you are not a transsexual. You are a transvestite. You may even be suspected of being a homosexual,” says a religiously conservative journalist addressing a transgender person at a clinic in the 2008 documentary exploring the lives of transgender Iranians, Be Like Others. “Make up your mind—either you want to be a girl or a boy,” she observes, then points to the crux of the issue. “It is my duty [as a Muslim] to know if someone is a man or a woman.

Many religious scholars, too, argue that a strict “filtering” process is necessary in order to mainain the distinction between the acceptable transsexual and the deviant homosexual. Najmabadi cites Mohammad Mehdi Kariminia, a university professor and cleric in Qom, who wrote his doctoral thesis on Iranian transsexuals, represents the dominant view when he insists that a “Great Wall of China” separates transsexuals from same-sex gamers. “Transsexuals are sick because they are not happy with their sexuality and so should be cured,” he says. “Homosexuality is considered a deviant act” and is punishable by law.

Najmabadi argues that the process of filtering has, paradoxically, created new social spaces for gay and lesbian Iranians—a “process that needs to offer a safe passage between categories.” She quotes one pre-op female-to-male transgendered person, “Once I was diagnosed as TS (trans-sexual), I started having sex with my girlfriend without feeling guilty.” Indeed, while the hardships and pressures on transsexuals should not be underestimated, neither should the creativity and determination displayed by sexual minorities who skillfully navigate the various institutions of power that try, and often fail, to determine their lives.

Amin takes a more cynical perspective. “How can someone go to a doctor, who is under control of authorities, and talk about their sexuality openly?” While she acknowledges that some people may use the “filtering” process to continue to pursue their same-sex relationships, she argues that, more often, homosexual applicants are persuaded to undergo permanent treatment (hormones or surgery), or risk other forms of abuse. “Show me one person who is officially living as a homosexual in Iran,” she says. “Show me one doctor who says, ‘You’re really homosexual. Now go in peace.’”

THE MARRIAGE IMPERATIVE

While there have been no documented cases of gay Iranians forced into undergoing surgery, it is clear that the pressure to move from a homosexual existence to a transsexual one, or something in between, is exerted from multiple directions. This is true even as the State is invested in maintaining a strict border between the two categories.

For some gays and lesbians in long-term relationships, the pressure to marry often contributes to the decision of one partner to transition to another sex as a last ditch effort to save the relationship. In other cases, people are persuaded to undergo a surgical transition after visiting a doctor or a run-in with a governmental official. During the course of its investigations into the situation of sexual minorities in Iran, Human Rights Watch spoke to Payam S., who identifies as a gay male, and he explained how his psychiatrist tried to convince him to undergo surgery:

I went to a psychiatrist on my own who helped me. At first, she said, ‘you are a transperson, and you can easily change.’ I told her I am a man, and I will not change. I like men, but I want to be with men as a man not as a woman. I have no problems with my manhood. I knew I would never do this. Despite this, she never used the word ‘gay.’ She just called me a ‘weak trans.’

Due to its religious sanction, other applicants are tempted by sex reassignment surgery, especially those who are devout Muslims. In her book, Najmabadi traces the interaction between religious and medical discourses, which led to the religious sanction of sex change operations for transsexuals. Long before Khomeini’s fatwa, classic Islamic discourse categorized every human body as either male or female, acknowledging the possibility that sometimes it may be difficult to determine the body’s true sex, as in the case of hermaphrodites. Determining bodies as either male or female is of paramount importance, however, because a moral society depends so heavily on intricate rules governing relations between the sexes.

Medical advancements allowed for the “true” sex of an intersex subject to be determined and for corrective surgery to be administered accordingly. By the 1960s, a consensus emerged among Iranian clerics that sex change surgery was unequivocally acceptable for intersex conditions. Meanwhile, Iranian medical discourse on sexuality was being fundamentally reshaped by newly imported psychology and sexology texts that traveled from Europe to Iran. Not only did these texts introduce transsexuality as a medical condition independent of intersex conditions, they also brought a set of academic trends in psychology, medicine, and criminology that, like their counterparts in Europe and America, linked sexual deviance with mental illness and criminality. Such publications would often describe male homosexuality as violent, akin to rape, prone to murder, and almost always aimed at youths. Indeed, the equation of male homosexuality and rape remains strong today in Iran. In most cases where death sentences are issued for crimes involving same-sex acts, the actual conviction is for rape, often rape of under-aged boys, even if the guilty party is an under-aged boy himself.

While the previous religious discourse considered transsexuality as more closely related to intersex conditions, the medical discourse identified transsexuality more closely to homosexuality—implying that same-sex desires could be a sign of gender identity disorder, not homosexuality per se. In other words, the desired gender is a sign and symptom of one’s actual gender, and one can only be entirely male or entirely female, even if the manifestation of that sex is sometimes ambiguous. In most people, the argument goes, there is harmony between the two, but in a small number, a disharmony produces gender identity disorder. We cannot change a person’s soul, but medical advances have made it possible to alter a person’s body when necessary for physical, psychic, or moral health.

This concept may seem puzzling to anyone more familiar with a conservative Christian view of sex change operations, which prohibits them on grounds that changing God’s creation (i.e. the body) is sinful—a view also taken by many Sunni religious scholars, and hence far more broadly represented in the global Muslim community. “Trans-friendly” Shi’a scholars, largely in Iran, rationalize sex change surgery as just another in the many acts of transformation we undertake on a daily basis: “If changing your gender was to be considered a sin because you are changing God’s natural order, then all of our daily tasks would be sins,” argues one cleric speaking to a conference on transsexuality held by the Health Ministry in Gorgan. “You take wheat and turn it into bread. That’s a change! There are a thousand things we do every day that are changes in God’s natural order. Why is that not considered a sin?” He immediately follows up, however, by again insisting on the distinction between transsexuality and homosexuality. “This discussion [on trans- sexuality] is fundamentally separate from a discussion regarding homosexuals,” he says. “Absolutely not related. Homosexuals are doing something unnatural and against religion.”

CULTURAL SICKNESS

Contrary to popular belief, homosexuality is not criminalized in Iran. That is, same-sex attractions, desires, even identities are not illegal. What is criminalized is a particular set of sexual acts that occur outside of a sanctioned heterosexual marriage, including sodomy and adultery. Under certain circumstances, a man convicted of sodomy, or lavat, can be put to death. The method of execution is left to the judge’s discretion, but it is usually hanging. If the accused are underage, or if no penetration has occurred, the sentence will be converted to lashing. Lesbianism, or mosahegheh, is punished more leniently than same-sex relations among men—an unusual feature in a legislative code that so regularly discriminates against women. Here the punishment is also lashing, but anyone convicted of homosexual acts for a fourth time, regardless of gender, will be sentenced to death.

It is often said that Iran’s penal code is based on shariah, or Islamic Law—the unchanging and immutable totality of God’s commands as revealed through the Prophet Mohammad. It is more correct to say that punishment is based onfiqh, or the tradition of Islamic jurisprudence. Fiqh literally means “understanding”—that is, the human understanding and interpretation of divine shariah. The distinction between shariah and fiqh is crucial, according to Islamic scholar Ziba Mir Hosseini, because “some specialists and politicians today—often with ideological intent—mistakenly equate shariah with fiqh and present fiqh rulings as shariah, hence as divine and not open to challenge.” All of which suggests just how contradictory modern day interpretations of Islamic law can be. In fact, early Muslims’ relationship to homosexuality was paradoxical. Superficial intolerance of sodomy was derived from the Quranic story of Lut (equivalent to the biblical Lot), even as pederasty and love between men was celebrated in poetry, art, and literature. Persian poetry, in particular, featured a significant amount of homoeroticism, with references to sexual love in addition to spiritual or religious love present in these relationships. Moreover, in most parts of the Islamic world, including Iran, as long as men (whose sex lives we know much more about) performed their “procreative obligations,” the larger community was generally not much concerned with the rest of their sex lives, according to Najmabadi.

Attitudes toward homosexual relationships began to change, however, during the Pahlavi era (1925 through 1979), when a range of policies was implemented that aimed to transform Iran from a dependent, traditional society to a modern, independent nation-state with Europe as its model. Iran criminalized sodomy as an effort to encourage a European-style nuclear family and sexual sensibilities. The 1979 Iranian Revolution suggested that infiltration of the family unit constituted one of the most potent modes of cultural imperialism conducted by Western forces to control Iran. Thus, one of the very first tasks after the Revolution was the repeal of the Shah’s personal status and family laws, substituting new penal codes as part of an overall “anti-corruption” campaign to cleanse the post-revolutionary society of any infiltration of “Western” gender relations, especially sexual transgressions such as adultery, fornication, prostitution, and homosexuality. Sex outside of marriage became punishable by stoning. In fact, the crime of adultery still warrants greater punishment than the crime of murder in the Islamic Penal Code (created in 1983), since it’s considered a crime against the foundations of the new Islamic state.

These days, however, the official discourse on sexuality has increasingly gone medical. “In the last 10 years, whenever the government or media talks about sexuality, they talk about a kind of health or psychological problem—gender identity disorder,” Amin says. “Everything is about gender identity disorder. And if you have it, there’s one solution—go and change your sex.”

KHOMEINI, KHAMENEI, FREUD

While religious edicts, particularly Khomeini’s fatwa, deserve the most credit for legalizing transsexuality, the medical community has played the largest role in making transsexuality a legitimate health problem while maintaining homosexuality as deviant and criminal. Indeed, though, the treatment of transsexuality and homosexuality in Iran more closely resembles mid-20th century American and European moral, legal, and medical discourse than early Islam.

Far from eschewing modern scientific, medical, and technological innovations, the architects of the Islamic Republic attempted to integrate these systems of knowledge as part of their attempts to build a “modern Islamic state,” a process known inside Iran as intebaq (compliance). Najmabadi puts it aptly when she describes an Iranian medical conference she attended in 2006: “On one wall were the jointly framed portraits of Ayatollahs Khomeini and Khamenei—a familiar sight in all state buildings and many private businesses. On an adjacent wall was a portrait of Freud.”

Najmabadi further explains how the consensus between the medical and religious communities over transsexuality is one of the most celebrated accomplishments of compliance in post-revolutionary Iran. Doctors reiterate and take pride in the distinction between homosexuality and transsexuality—only they articulate such difference with a medical, not religious, lexicon. Not only does the Iranian medical community support such a distinction, there is evidence to suspect they profit from it. In the last decade, the health industry surrounding sex change surgery has been booming. A number of clinics have opened specifically to serve transsexual patients, mostly in Tehran. Iran has assumed the unlikely role of global leader for sex change, even becoming, asThe Guardian observes, “a magnet for patients from eastern European and Arab countries seeking to change their genders.” The increase in public disclosure has in turn led to more operations—Najmabadi reports that many transsexuals, especially those coming from provincial towns outside Tehran, find out about such clinics and state support of transsexuals through press coverage.

Some doctors have built entire careers from sex change surgeries, rising to international fame as “heroes” of the Iranian transsexual community. Interviews, documentaries, and memoirs featuring these doctors often refer to their power to “fix” nature’s mistakes and “save” nature’s victims, at times bordering on the megalomaniacal. In one memoir titled Purgatory of the Body: Surgeon’s Memoirs of Transsexuals in Iran, Dr. Shahryar Cohanzad writes: “For years I have channeled my knowledge and experience into developing surgical techniques capable of delivering these vagabonds of existence from dark and ambivalence. . . directly shoulder[ing] the lofty responsibility of rectifying this error of the not-that-much- flawless nature.” And in the documentary Be Like Others, Dr. Bahram Mir Jalali takes credit for solidifying the trans/homo distinction and legalizing transsexuality in Iran. “It is curious that homosexuality is a capital crime and outlawed and severe punishments like stoning are handed out,” he observes. “Why then do they give per- mission to transsexuals? I can tell you that one of the pioneers of this way of thinking about transsexuals in the last 20 years has been me.”

Atrina, a 27-year-old transwoman who believes many transgender Iranians desperate to have sex change surgery are exploited, tells Human Rights Watch:

There are some doctors who take advantage of friends who do not have the money to pay for surgery. These doctors do not care whether patients really know whether they want to or should change their sex, whether the surgery is carried out properly, or what the possible complications are. There are doctors who are able to lower the price for surgery but instead keep raising the prices and sell themselves under false pretenses. Trans patients are like steps that these doctors use to climb toward profits.

The latest trend among this medical community is “aversion therapy” for homosexuals—inspired yet again by American psychiatric researchers who routinely performed the treatment in order to eliminate homosexuality in the 1960s and 1970s. Aversion therapy usually involves exposing the patient to some kind of stimuli, such as homoerotic photographs, while simultaneously putting the patient under duress, shock, or pain. A recent article in the Iranian Journal of Forensic Medicine reports on “successful” cases of ex-homosexuals cured with aversion therapy. American Psychiatric Associations and the World Health Organization, meanwhile, have condemned aversion therapy as a means of altering sexual orientation.

POST-CURE TRAUMA

Despite the broad approval of transgenderism and surgical solutions among Iran’s medical, religious, and government officials, it is clear that Iranian society is still hostile to the idea of transsexuality. Indeed, Iranian transpeople face many of the same challenges as their Western counterparts—rejection by their families, difficulty holding steady employment, sexual violence, police abuse, social stigma, and depression. A significant number of transwomen, in particular, resort to sigheh—religiously-sanctioned “temporary marriages”—in order to survive. The majority of Iranian society considers these temporary marriages to be a form of legally-sanctioned prostitution, as they usually involve the exchange of sex for money for a specified amount of time, the minimum being one hour.

While the Iranian government continues to invest in the medical infrastructure supporting sex change surgery, there is very little support for post-op patients, and even less for families of transpeople. Even if parents permanently shun their transgendered offspring, they often face immense shame from neighbors and coworkers. Families often find it easier to move to a different neighborhood or town where no one knows they have a transsexual son or daughter.

Though most narratives tend to focus on male-to-female changes, probably due to an especially strong stigma against passive gay men, Amin emphasizes that female-to-male transpeople face their own share of burdens. She relays several stories of “butch” lesbian women who transition only to have their “femme” partners leave them for “real men” post-surgery. And because female-to-male surgery is so complex and expensive, many transmen are left in an incomplete stage of transition.

In the end, the greatest source of support for transsexual Iranians is one another. Transsexuals tend to find each other and form alternative family relationships and support communities. Often they will live together and help one another find employment, get medicine (especially hormones bought on the black market), and navigate legal and bureaucratic pro- cesses. The Internet has been particularly helpful in this regard. A number of online groups have formed to provide transgender (and homosexual) Iranians mutual support, especially for those who live outside Tehran. While many discussions on these forums focus on everyday survival, they also provide a platform for activism and political strategizing.

ACTIVISM, ALLIANCE, AMBIVALENCE

On these online forums and in other safer spaces, activism around sexual minorities in Iran takes shape. While authorities may have the means to track people’s Internet usage, they rarely have the will to prioritize these online forums, allowing for relatively freer association. Indeed, new and stronger alliances between transsexuals and gay Iranians have begun to emerge in recent years. But the lessons derived from these alliances remain unclear, especially as they relate to Western policy toward the rights of Iran’s gay, lesbian, and transgender communities.

As Najmabadi writes, “While identity struggles have raged within transnational diasporic Iranian communities, many gays, lesbians, and transsexuals in Iran wish to keep national and international politics out of their daily lives.” These days, many Iranian transpeople are outright resistant to international exposure of their lives and struggles, seeing such efforts as potentially detrimental to the needs of Iranian transsexuals themselves. All too often, they see Iranian transsexuals transformed into objects of pity, while decades of transactivism are ignored in favor of an exclusive focus on state and religious institutions.

Other commentators have insisted on the danger of Western intervention in the sexual politics and identities of Iranians. Scott Long, former director of the LGBT Rights Program at Human Rights Watch, argues that gay and lesbian activists in the West often reduce the context of rights violations in Iran in search of a gay identity and for homophobia. Not only are such labels often inappropriate (in many cases, the person at the center of controversy does not identify as gay), they can be deadly. The practice of homosexuality is, after all, a capital crime in Iran. Long also points to the sweeping characterization of religion, culture, and especially Islam in this style of activism, reducing all mistreatment of sexual minorities to the assumption that “Islam hates gays.” Many misguided Western LGBT activists portray Iran, and Islam in general, as homophobic—a stereotype that fails to conform to most realities.

Many Iranian activists, however, remain open to the possibility of an internationally-embedded queer political movement in Iran, even if such activism does constitute a Western import. “We [Iranians] import everything,” Amin says. “We import cars. We import medicine. Who says we can’t import human rights? It doesn’t matter to me where they come from.” And then there are those who find the most promising avenue toward change in the same institutions that many outsiders blame for the predicament in the first place—religious interpretation, medical knowledge, and piecemeal reforms within Iranian domestic politics.

If a common consensus exists over the question of protecting sexual minorities in Iran, it is that the people leading the effort should be the ones most affected. Considering the many paradoxes characterizing the situation of lesbian, gay, and transgender people in Iran, only they have the requisite knowledge and insight to spark positive change. In fact, the involvement of foreign parties, particularly from the United States or Europe, may sabotage local efforts. Such involvement may reinforce pernicious stereotypes that sexual rights constitute a Western import. Instead, indigenous movements for sexual rights are lobbying for practical but desperately needed concessions, such as access to housing, medical care, and protection from police harassment. They are also taking strategic advantage of the current debate over transsexuality to move the conversation away from the dominant discourse centered around sex change operations.

Indeed, the most promising avenue for change might just be cultural—gently opening the conversation of sexuality beyond the governmental discourse of sex change operations and gender identity disorder and into taboo topics such as sexual orientation. Considering Iran’s highly engaged, open-minded youth bloc—60 percent of Iran’s 73 million people are under 30 years old—some forms of cultural change might come sooner than anyone expects. If Middle Eastern politics over the last five years has taught us anything, it is that once- hopeless causes can change overnight. And when it comes to sexuality in Iran, what is considered taboo today could well be encouraged tomorrow.

*****

Rochelle Terman is an Iranian-American Ph.D. candidate in Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley and sits on the advisory council for Women Living Under Muslim Law’s International Solidarity Network.

[Photo courtesy of AP]

This piece was originally published by World Policy here.