#May28: Continuing the Struggle for #SRHR4All and #WomensHealthMatters

The Women’s Global Network for Reproductive Rights’ campaign for women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) this year holds a curious coincidence: it is their twenty-eighth campaign, set for the twenty-eighth of May.

For these past twenty-eight years, WGNRR has been vigorously campaigning for a change in government policies towards institutional violence, abortion rights, forced sterilizations, obstetric violence, and access to contraceptives and family planning strategies. Almost three decades have gone by with these yearly campaigns; almost three decades of women’s rights activists gearing up, throwing their voices, holding up banners, demanding their equality have passed, and the years only continue to plod on.

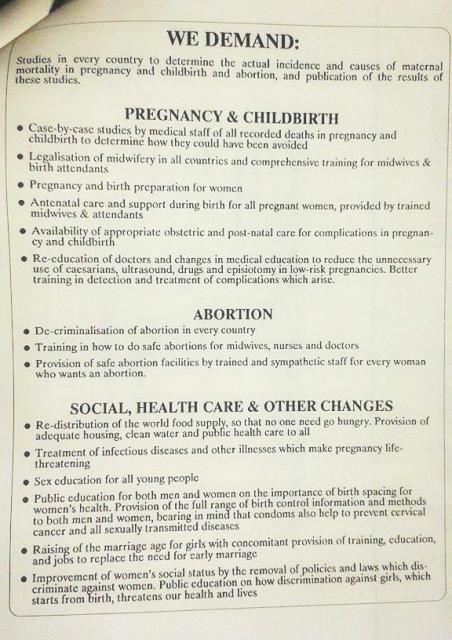

As we at WLUML set about resourcing information for the campaign, we stumbled upon another curious coincidence. Our interns, in the midst of combing through our library, found a leaflet from the same campaign from 1988—just one year after the movement had started. We immediately flipped through it together in a ripple of excitement that was promptly followed by a disheartened silence. Have a look:

“Governments have not made sufficient funds or training available to provide adequate health services to women”; “governments refuse to change their laws so that abortion is no longer a criminal and clandestine act”; “religious leaders...actively campaign against birth control and abortion—in the name of whatever religion—[and] condemn women to death”; and, with the most resonance, “among many people who have power over our lives and deaths, women’s lives don’t count.”

“WE DEMAND”, the leaflet continues, “de-criminalisation of abortion in every country”; “provision of safe abortion facilities”; ““sex education for all young people”; “public education...on the importance of birth spacing for women’s health”; “raising of marriage age for girls”; “improvement of women’s social status by the removal of [discriminating] policies and laws.”

The demands listed on that leaflet—when the enthusiasm had just begun, when the intensity was just gearing up—were disappointingly familiar.

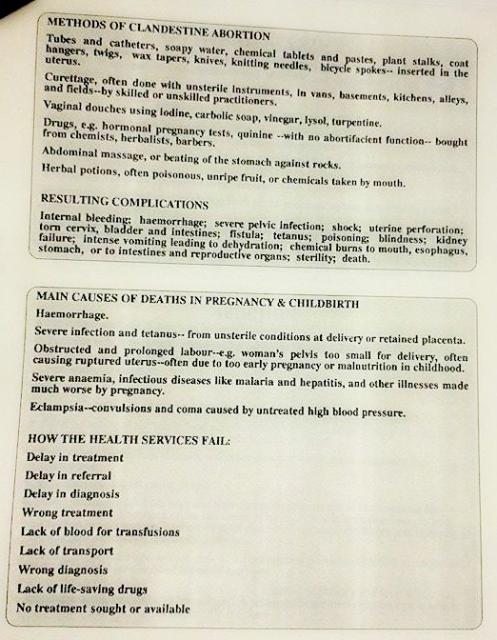

However, to leave the picture there would be unfairly reductive. 1988 looks similar to 2015, but we all know that progress rarely moves in a linear fashion. “The number of maternal deaths occurring reach year is most often quoted as 500,000”, 1988’s leaflet leaflet proclaims, adding that the real figure was probably closer to a million. An updated statistic, taken from WHO’s factsheet on maternal mortality in 2014, provides relief: “Since 1990, maternal deaths worldwide have dropped by 45%”, of which only 8% are concerned with “abortion complications”. In 2013, maternal deaths numbered at 289 000, a figure that, although certainly harrowing, does show significant reduction since the campaign started.

When the leaflet was printed in 1988, WLUML too was in its first years. It’s indeed fair to say that like the WGNRR, we continue to work on a lot of the same issues as we did then.

The most emphasized SRHR issues in Muslim contexts include Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), “honour crimes” and early/forced marriages, all of which have garnered a lot of international attention in the decades since. Big organizations have recognized the need to face these issues, and have actively worked their way to campaign against them.

Like the WGNRR however, the progress has not been linear. Despite the increased attention on FGM, “honour crimes” and early and forced marriages, these issues are still at the forefront of our fight today. Some of the factors infringing on women’s sexual and bodily rights have actually worsened since the 1980s. The revival of zina laws (which criminalise sex outside of marriage), for instance, has had a hugely deleterious effect on women, having ensured a systematic, state-sanctioned route to control women’s sexualities and rights to love. Lashings, death by stoning and other corporal punishments threaten these “transgressors”. SRHR issues also take the form of enforced dress codes as they tighten a grip over women’s bodies, distort morality discourses, institutionalise sexism and instil a culture that encourages victim-blaming.

Yes, we are aware of the dismal state of affairs. We have seen authorities deny women their SRHR using morality, tradition and religion as justification. In Indonesia, we have seen the commander of the armed forces condoning the implementation of forced virginity tests on female recruits, saying “it is a good thing...it’s a measure of morality.” In South Africa, we have seen girl brides kidnapped and raped for decades by men with HIV in the misguided belief that virgins cure their disease. Afghanistan has shown us the criminalization of women who have been raped or forced into prostitution, labelling them adulterers. We have seen, overall, a rise in fundamentalisms, and it has left a sense of urgency in us that goes up with every disheartening piece of news.

Those that dare to stand up and speak out against the taboos of sexuality face violent backlash. Gambian campaigners Isatou Touray and Amie Bojang-Sissoho were persecuted by the government because of their anti-FGM work. In Sri Lanka Sharmila Seyyid has been mercilessly harassed for speaking up for sex workers’ rights. Militant extremists in Pakistan shot Fareeda Kokikhel for promoting women’s rights in the northwest province. The list goes on.

But to say there has been no progress would be not only disrespectful, but also a lie. Yes, we have a long way to go. However, let’s not forget the small victories that have occurred in the past few years.

Our “Women Reclaiming and Redefining Cultures” programme helped to change the discourse on women’s sexuality across Nigeria, Senegal, Indonesia, Turkey, Afghanistan, Thailand, Sudan and Morocco. The Center for Advancement of Development Rights in Nigeria got the Reverend Father on board with their project on increasing sex education for women. An initiative in Indonesia moved to reclaim women rights on sexuality, spawning organizations of activists, academics, and NGOs who have pledged to re-programme social perceptions of women.

Our partner in Gambia, GAMCOTRAP, held their third event Dropping of the Knife in 2011 to advocate against FGM, witnessing a public declaration by twenty circumcisers and support from 150 communities in just that year alone. And just three days ago we celebrated the news that Nigeria has criminalised FGM!

Last year we gathered over 12,000 petitioners to demand the UN OHCHR put an end to the practise of stoning women to death. GREFELS, in Senegal, met success in 2014 when they stopped a child marriage in its tracks with the help of their local partner APAM. BAOBAB gave ownership to Nigerian women at the grassroots of the struggle to end child marriage. Shirkat Gah in Pakistan brought together the Purple Women’s Movement in 2013, which has since drawn promises from politicians to increase women’s public participation, fight against domestic violence, and treat honour killings as crimes against the state.

Our Sudanese partner, Salmmah Women’s Resource Centre, has been at the forefront of a national alliance to change a law conflating rape with the crime of extra-marital sex. They saw some victory in March this year, as the law in question was changed—although other legal amendments and a narrowing of civil liberties have cast a dubious shadow over the success. Like we mentioned—progress: never a straight line.

Recent years have shown some exhilarating examples of women’s resistance. Lubna Hussein of Sudan was named one of the Guardian’s Top 100 women, after she was arrested for her “crime” of wearing trousers. She resigned as a press officer from the UN so that she could face the charge where her sentence could be 40 lashes, and has not faltered, despite various death threats. Sophia Jama of Algeria sparked a nationwide social media protest after being denied entrance into an exam for her ‘indecency’ of wearing a skirt that showed her legs. Thousands gathered in Kenya to protest the assault of a woman wearing a miniskirt. Masih Alinejad of Iran has launched the campaign ‘My Stealthy Freedom’, which has drawn crowds of Iranian women protesting against their enforced hijabs. Marianna al-Taabah has hosted family planning workshops for Syrian refugee women, despite the deep sensitivity around the issue. Marsa, a Lebanese sexual health centre, released a wonderfully audacious video featuring women speaking frankly about their bodies.

Commendable achievements, especially given the contexts in which they occur! These are movements shrouded in decades of taboo, and for them to have sprouted up the way they have makes us proud.

It is only by reminding ourselves of the little victories that we can manage not to be disheartened by the familiarity of the 1988 leaflet. It is only by highlighting all the instances of rebellion and defiance that we can we can envision a future that looks different.

One of our networkers, Mali’s award-winning campaigner Mariam Diallo-Drame, interviewed with us in February of this year: “Every day I make a positive difference to girls,” she told us. “We try to turn challenges to opportunities.” We asked her, if in these troubling times, she has any advice for activists in other countries. She responded:

“Hang on. The struggle for women’s rights is not a straight line. We can have painful moments, but we remain standing and strong because we are women, we are life.”

These words ring in our ears —we cannot let the rising threats make us waver.

Our hope, like the WGNRR’s, is that we will eventually see a day without #InstitutionalViolence. A day without #ForcedSterilisation, #ObstetricViolence, and with #SafeAbortion. Women in all parts of the world will no longer feel a tight grip over their sexuality; they will walk down the street wearing what they want, will choose who to love, will have the power to decide if and when to bear children, will not suffer mutilation justified by culture or religion of any kind.

Twenty-eight years of #May28 have instilled in us the belief that #WomensHealthMatters. Let’s not disappoint the campaign, or let stagnancy and backlash disappoint us. Change is possible—it starts with us.

By Ifra Asad